The art of ‘staying present’ involves refining the qualities of paying attention and tracking energy flow. Whether we are noticing the inner movements of the body-mind or the flow of society, culture and the cyclic rhythms of the natural world, finding a still center to feel the dynamic fullness of presence is challenging, to say the least. But as we unpack the multiple levels of our moment to moment experience, we discover our primary or foundation level is an ongoing flow of energy, also called prana or qi. When our attention lands on and rests in this breathing flow, two significant results follow.

The art of ‘staying present’ involves refining the qualities of paying attention and tracking energy flow. Whether we are noticing the inner movements of the body-mind or the flow of society, culture and the cyclic rhythms of the natural world, finding a still center to feel the dynamic fullness of presence is challenging, to say the least. But as we unpack the multiple levels of our moment to moment experience, we discover our primary or foundation level is an ongoing flow of energy, also called prana or qi. When our attention lands on and rests in this breathing flow, two significant results follow.

First, because our attention is occupied by tracking/feeling the sensations of breath as they arise and fall in the present moment, we do not get lost and entangled in thoughts of past or future. Secondly, attention carries its own form of energy. This energy flow can strengthen both the vibrancy of the breathing sensations and our capacity to return to the sensations when the mind inevitably wanders to some other information stream. This second result is actually a restating of the important principle in neuroscience known as ‘Hebb’s Axiom: ‘Neurons that fire together wire together’. The process of sustaining attention literally re-wires the brain.

In any given moment there are a myriad of information streams clamoring for our attention. When we begin a meditation practice, it does not take long to realize that our attention seems to be continually hijacked by unconscious tendencies, as the mind jumps from one thought to another. Meditators call this the ‘monkey mind’ and the first step in meditation is not stopping this tendency, but just noticing it. This is the point where beginners get into trouble as they often begin with the false notion that meditation is about making the mind quiet down. The effort to quiet the mind just creates more frustration and mental activity.

By observing the wandering mind without resistance we create some mental ‘space’ where we can be curious and compassionate about what is actually happening moment to moment. We begin to realize that there are underlying anxieties leading the mind to habitually be busy. We kindly and gently offer it the task of attending to the breathing, with an intention to return our attention back to the breathing whenever we notice we have gone off track. Once, a hundred times, a thousand times, whatever is necessary. This practice is known as dharana in Sanskrit. Over time, the breathing flow settles the mind into a relaxed, focused and gentle rhythm known as dhyana. (When the meditative practices of Buddhism moved from India into China, dhyana became ‘Chan“, and when ‘Chan’ practice reached Japan it became Zen.)

As we sit, our curiosity can also notice what subjects/thoughts are the most likely to hijack our attention and we can discover ways of handling these tendencies. Sitting first thing early in the morning, before we have become engaged in the tasks of the, day is very helpful because the mind is still resting from the nights sleep. Also, just having the intention ‘I know there is a lot going on in my life, but for the next few minutes, I am going to put everything aside, in full confidence that I will be able to still do what needs to be done later’, allows a level of relaxation and a softening and opening of the mental space. In time, moments appear where attention finally just rests, and all that remains is Pure Awareness.

Whenever we are sitting, sustaining the attention only on the breathing sensations and then allowing the attention process to rest is anything but easy. Discipline, patience, self kindness and a sense of humor are necessary tools to progress on the path of meditation. As our meditation practice expands to the somatic level, we learn to sustain our attention using deeper and more subtle sensations of the breathing/qi/prana that can be felt in the fluids, organs and tissues.

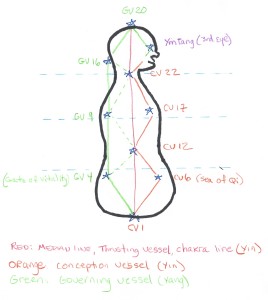

As mentioned previously, attention carries energy. By integrating into our field of attention specific points and pathways of the subtle qi such as those of the ‘Microcosmic Orbit’ and other meridians and vessels, we can increase the vibrancy of the flow of prana/qi and thus the vibrancy and health of the overall human energy field.

As mentioned previously, attention carries energy. By integrating into our field of attention specific points and pathways of the subtle qi such as those of the ‘Microcosmic Orbit’ and other meridians and vessels, we can increase the vibrancy of the flow of prana/qi and thus the vibrancy and health of the overall human energy field.

As our capacity to sustain attention in the qi field increases, the old habits of distraction lose their ability to capture our full attention. As per Hebb’s Axiom, their neuronal pathways are no longer being fully fed and the habits (samskaras in Sanskrit) begin to loose their karmic momentum. Think of these energetic habits like a burning camp fire. As long as we keep feeding the fire it will burn. More fuel means more heat. Less fuel and eventually no fuel and the fire burns itself out. The same can happen for all of our unhealthy habits if we can learn some restraint (nirodha in Sanskrit). However, restraint is not repression. Repressing the habitual patterns into the unconscious also fuels them, so we allow them to arise in presence, but leave them be, without attending to them/feeding them.

Finally, in learning to stay ‘present’ through meditation, and diving deep into its roots, we discover a portal into the infinite, a glimpse of the unchanging presence of Awareness, the source or context in which all of the mental activity arises and dissolves. It may be felt as ‘stillness’, ‘silence’ or a vast open spaciousness. It is Awareness prior to any arising of thought or sensation. ‘This Awareness’ is already and always present.

With time we can recognize the habit of mistaking the mental processes that come and go for our True Self, the always and already present Awareness. We see that when our self – identity (ahamkara in Sanskrit) is tied up in thoughts and beliefs, (PYS I-4), we create suffering for ourselves and others. When we can dis-entangle our identity from mental activity, we begin to rest in Awareness. We do not ‘do’ awareness, nor do we try to understand it. That is just more mental activity. Just as we relax into falling asleep, we relax into falling Awake. As Patanjali says in sutra I-3, we rest in the truth of our selves, drashtuh svarupe or as the Chinese would say, we rest in the Tao.

*****************************************

In Dan Siegel’s ‘Wheel of Attention’ meditation practice (see below), we utilize all the major information steams to explore attention and inner stillness. (from a previous blog post)

We will begin with Dan Siegels’ ‘Wheel of Awareness meditation, to get a feel for the territory of mind, mind activity, and mind states. In the ‘Wheel of Awareness, meditation exploration, we use the wheel as a visual metaphor of the mind. Around the rim of the wheel representing the world of form, are located the spokes representing the various information streams that feed the brain. These include the five outer senses: sight,  hearing, taste, smell and touch: the two inner senses of kinesthesia which feeds information from the muscles, bones and joints about location and movement: and proprioception, where we feel the motility or inner movements from the organs and fluids, driven by breathing, the heart beat, peristalsis and the cranio-sacral rhythms: our emotional energies percolating up from the cells and organs: the cognitive (word based) energies including the ‘monkey mind’; and a felt sense of ‘other minds’ that arise in all of our relationships. These sources stream energy and information from the metaphorical rim, to the hub, along the ‘spokes’ and we use the hub to locate/represent ‘pure awareness’. (Warning! All metaphors are limited. Useful but limited. Awareness is not confined by space or time.)

hearing, taste, smell and touch: the two inner senses of kinesthesia which feeds information from the muscles, bones and joints about location and movement: and proprioception, where we feel the motility or inner movements from the organs and fluids, driven by breathing, the heart beat, peristalsis and the cranio-sacral rhythms: our emotional energies percolating up from the cells and organs: the cognitive (word based) energies including the ‘monkey mind’; and a felt sense of ‘other minds’ that arise in all of our relationships. These sources stream energy and information from the metaphorical rim, to the hub, along the ‘spokes’ and we use the hub to locate/represent ‘pure awareness’. (Warning! All metaphors are limited. Useful but limited. Awareness is not confined by space or time.)

From the ‘hub’ of awareness, we direct our attention out the various ‘spokes’ to observe what is arising. We may notice the the process of ‘attention’ has a mind of its own and may jump from one spoke to another. Our discipline, (abhyasa), is to help stabilize attention, by bringing it to a specific spoke (dharana), keeping it there with some mindful effort (dhyana), and eventually having this become effortless (samadhi). Also we can cultivate a flexible attention that we can use efficiently as we take in the world without being ‘distracted’ by random sensations or thoughts.

In the ‘wheel of awareness’, we go back and forth, from the ‘hub of awareness’ to the various modalities out on the rim. What is most helpful is to really rest in the hub in between trips to the rim. Here awareness rests in itself. Awareness, not needing any information/objects of attention to sustain it, is still, open, unbounded by space and time, and aware. Patanjali calls this drashtuh svarupe’ the seer resting it its own inherent nature, and uses this to describe the result of yoga. (PYS, I-3). Eckhart Tolle use the term ‘Now’. Atman, Brahman, Presence, Primordial Being are some other ‘pointing’ words. You can also use your open heart as the silent center.

By resting in awareness, we learn to not be so reactive to what arises, so we begin to tease apart the many layers of reactivity that comprise the ‘vrttis’ Patanjali describes in the Samadhi Pada. We see the ephemeral nature of thoughts, beliefs, ideas, sensations and slowly disentangle our ‘self-sense’ from this transient world.

In a somatic based practice like hatha yoga, the information streams coming from the kinesthetic and proprioceptive streams are cultivated, studied and refined. We learn to feel our way through the body and allow the wisdom of the body to reveal itself moment to moment. Most yoga students begin with the mind telling the body what to do because they have never been taught how to feel, how to listen to the body. As teachers we need to help the students develop the confidence to trust what they feel and to not be afraid of sensations that are less than pleasant. Those sensations are our teachers.

It is also important to be able to observe the functioning of the mind. Remember, in our wheel metaphor, the pure awareness of the hub is not mind activity, or as Patanjali describes, citta vrttis. We can watch and study the movement and layers of mental activity, if we can slow down and be patient. Yogis have been mapping mental states for thousands of years, and poets and saints have described the ecstasy of a divinely opened  heart. Their experience is incredibly beneficial for us all and the invite us to join them. As the mystical poet Rumi wrote 800 or so years ago,

heart. Their experience is incredibly beneficial for us all and the invite us to join them. As the mystical poet Rumi wrote 800 or so years ago,

“Out beyond the ideas of right doing

and wrong doing there is a field.

I will meet you there.”