See also previous posts from Detroit (Mobility, Motility, Stillness) and Concentric Circles 1, 2, and 3.

Key topics covered and more….

Meditation Practices

Opening meditation: Find your central channel, let it relax and open. Imagine a line of energy passing down from the heavens, through your crown chakra, through your core, through your root chakra and on into the earth. Allow the energy to also flow from the earth upwards through your core into the heavens. Feel the center channel filled with light. Now feel your weight and allow the earth to meet you. Let every cell and bone feel its own weight and surrender into the earth. From the downwards flow of weight on into the earth, allow a felt sense of lightness, of levity to also be felt by every cell, every bone, so the body feels as if it were floating, suspended, relaxed and alert. Feel alive.

Now notice your breathing. Allow the in breath and out breath to both flow effortlessly. Dissolve the boundaries of the skin and feel the body suspended in breath, floating in breath. Now bring your attention to you heart center, the center of all center of all centers, and let it rest there poised, balanced, still. Feel the stillness expanding, dissolving time and space, and rest in the infinite spaciousness. Now imagine a sphere of light surrounding you, with your heart as the center. Feel like an embryo in a womb or egg. Be nurtured by the light. Let it penetrate into your cells and let your cells radiate their own light outward. Rest in the infinite spaciousness, the all pervasive luminous emptiness of your own divine nature.

Wheel of Awareness: In Dan Siegel’s meditation exploration, we use the wheel as a visual metaphor of the mind. Around the rim of the wheel are located the various sources of the information streams that feed the brain. These sources include the five outer senses including sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch; the inner senses of proprioception and kinesthesia which feed information from the muscles, bones and joints about location and movement; the sense of motility from the organs, much of which is driven by the breathing; our emotional energies percolating up from the cells and organs; and the cognitive (word based) energies including the ‘monkey mind’. These sources stream to the hub along the ‘spokes’ and we use the hub to locate ‘awareness’. (Warning! All metaphors are limited. Useful but limited. Awareness is not confined by space or time.)

From the ‘hub’ of awareness, we direct our attention out the various ‘spokes’ to observe what is arising. We may notice the the process of ‘attention’ has a mind of its own and may jump from one spoke to another. Our discipline, (abhyasa), is to help stabilize attention, by bringing it to a specific spoke (dharana), keeping it there with some mindful effort (dhyana), and eventually having this become effortless (samadhi). Also we can cultivate a flexible attention that we can use efficiently as we take in the world without being ‘distracted’ by random sensations or thoughts.

In the ‘wheel of awareness’, we go back and forth, from the ‘hub of awareness’ to the various modalities out on the rim. What is most helpful is to really rest in the hub in between trips to the rim. Here awareness rest in itself. Awareness, not needing any information/objects of attention to sustain it, is still, open, unbounded by space and time. Patanjali call this drashtuh svarupe’ the seer resting it its own inherent nature, and uses this to describe the result of yoga. (PYS, I-3). Eckhart Tolle use the term ‘Now”. Atman, Brahman, Presence, Primordial Being are some other ‘pointing’ words.

By resting in awareness, we learn to not be so reactive to what arises, so we begin to tease apart the many layers of reactivity that comprise the ‘vrttis’ Patanjali describes in the Samadhi Pada. We see the ephemeral nature of thoughts, beliefs, ideas, sensations and slowly disentangle our ‘self-sense’ from this transient world.

In a somatic based practice like hatha yoga, the information streams coming from the body/mind are cultivated, studied and refined. We learn to feel our way through the body and allow the wisdom of the body to reveal itself moment to moment. Most yoga students begin with the mind telling the body what to do because they have never been taught how to feel, how to listen to the body. As teachers we need to help the students develop the confidence to trust what they feel and to not be afraid of sensations that are less than pleasant. Those sensations are our teachers.

Meditation in Asana: Monitor and Modulate

Dan Siegel defines the mind as a self-organizing, emergent process that regulates the flow of energy and information within the body and within our relationships. Regulation is monitoring and modulating, monitoring and modifying. As this process strengthens, the mind strengthens, integration and coherence strengthens, and health and maturity emerge. This is Yoga! This is what we teach and practice. We use the poses as vehicles to deepen integration in the mind/body. This is why attending to what the body is saying is crucial. Moment to moment we are linking the attentional regions of the brain with the perceptions, proprioceptions and the motor regions (the movement brain) so they become integrated, acting as a whole. Hebbs Axiom, neurons that fire together wire together, gives us a huge clue about why mindful attention to our practice is effective.

Beginning students try to think or remember their way through a pose. Refined practice requires self monitoring while exploring. What happens if I turn this foot out just a bit? What happens if I change this? Of course this involves pausing, noticing , feeling and not just doing. Perception must be cultivated, our perceptual field must keep expanding, if we are to grow as students and teachers. Iyengar calls this posing and then re-posing, but it is meditation in the posture.

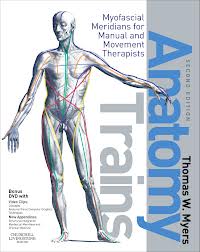

Anatomy Trains

Tom Myers has developed a fascial  mapping of the body that can be very helpful to yogis when seeking the energy lines that are integrative. We begin, as yogis, with the inner most line, the ‘deep front line’, as it integrates the visceral endoderm, the structural endoderm and the attentional ectoderm. No wasting time! It begins on the soles of the feet, travels up the deep calf, the adductors, hops onto the ilio-psoa muscles, joinds the diaphragmm pericardiam, inner chest cavity and throat. In tadasana, and all the standing poses we active this line in a slight plantar flexion action to awaken the soles. By using the wall and slowing down we can differentiate the deep front line (pressing down through the fronts of the feet) from the superfical back line (pulling up the heel bone. ) Find the metatarsals and tarsals including the navicular and cuboid (the balance bones), the talus and calcaneus bones. Feel waves of energy flowing through the feet. In triangle, parsvakonasana and ardha chandrasana, find the DFL as an extension through the back inner heel, inner leg and inner groin, as if pushing off on an ice skate. If you can, connect to the diaphragm and on into arms and skull. If you can, by-pass muscles and bones and extend from the energy line defined by the DFL.

mapping of the body that can be very helpful to yogis when seeking the energy lines that are integrative. We begin, as yogis, with the inner most line, the ‘deep front line’, as it integrates the visceral endoderm, the structural endoderm and the attentional ectoderm. No wasting time! It begins on the soles of the feet, travels up the deep calf, the adductors, hops onto the ilio-psoa muscles, joinds the diaphragmm pericardiam, inner chest cavity and throat. In tadasana, and all the standing poses we active this line in a slight plantar flexion action to awaken the soles. By using the wall and slowing down we can differentiate the deep front line (pressing down through the fronts of the feet) from the superfical back line (pulling up the heel bone. ) Find the metatarsals and tarsals including the navicular and cuboid (the balance bones), the talus and calcaneus bones. Feel waves of energy flowing through the feet. In triangle, parsvakonasana and ardha chandrasana, find the DFL as an extension through the back inner heel, inner leg and inner groin, as if pushing off on an ice skate. If you can, connect to the diaphragm and on into arms and skull. If you can, by-pass muscles and bones and extend from the energy line defined by the DFL.

Then, find this line extending out through the back foot in ardha and parvrtta ardha chandrasana, one legged dog, and the front walk-over into had stand. In the hand stand, use the lengthenning back leg to provide the power and lift. Let the hands land gently.

Matsyasana, Uttana Padasana the Sphenoid Basilar Junction

and the Superficial Front Line (SFL)

We want to open the upper portion of the SFL to help liberate our sense of the fish body, the spine without limbs. Begin lying with the knees bent. Roll the pubic bones towards the floor, lift the chest upward (without contracting the spine) and allow the skull to come into extension, chin rising up, like in fish pose.  This will create a beautiful arc in the SFL. feel the double action of the two ends moving away from each other. This may not happen naturally in the beginning, as the DFL might shorten and pull the chin down. Try using a bolster and/or rolled up blankets to create this action. Keep the lumbar muscles relaxing. Or you can try starting from matsyasana,

This will create a beautiful arc in the SFL. feel the double action of the two ends moving away from each other. This may not happen naturally in the beginning, as the DFL might shorten and pull the chin down. Try using a bolster and/or rolled up blankets to create this action. Keep the lumbar muscles relaxing. Or you can try starting from matsyasana,  using the forearms to lift the chest and extend the neck, lengthening through the sphenoid basilar junction at the base of the skull

using the forearms to lift the chest and extend the neck, lengthening through the sphenoid basilar junction at the base of the skull .

.

When we add the arms and legs in uttana padasana we get to further release the back muscles. This is an excellent way to discover the layers of the throat and neck and open the anterior portion of the body. We’ll save the full cervical extension, setu bhandasana, for another (life) time.

we get to further release the back muscles. This is an excellent way to discover the layers of the throat and neck and open the anterior portion of the body. We’ll save the full cervical extension, setu bhandasana, for another (life) time.

Here is an image to help unfold the endodermic intelligence. The diaphragm feels a lot like a jelly fish. The brain looks a lot like one! Mother Nature, loving to repeat shapes that work, uses this in the arches of the feet, the roof of the mouth flowing down the throat, the nasal passages curling across the floor of the skull and down into the throat, the aortic arch, and even, in a subtle way, in the one way valves of the venous and lymphatic vessels. Find the flow of energy (metaphor alert!) as the jellyfish undulates rhythmically. Trace it across the upper membrane and along any of the tentacles you can find.

Breathing Investigations.

Can we learn to differentiate ribs, spine, diaphragm, abdominal wall and head in breathing work? The average person off the street has a very tight restricted diaphragm and a breathing pattern that strains to breathe by trying to lift the rib cage up. This tightens the spine and the throat as well. This is why in singing and relaxation classes, students are taught to not use the ribs to breathe, but to use the diaphragm. This is called diaphragmatic breathing.

Yogis have no problem with this, but go much further. We use the standing postures to help open the diaphragm tremendously by linking it to the illio-psoas muscles and the lower DFL all the way to the feet. Groin opening postures are ideally diaphragm opening postures. We use bridge pose (and other back-bending poses)  to use the DFL to further expand the diaphragm up into the chest and open the intercostal muscles. All of these will help soften the throat and eliminate the need to use the face and neck muscles in breathing.

to use the DFL to further expand the diaphragm up into the chest and open the intercostal muscles. All of these will help soften the throat and eliminate the need to use the face and neck muscles in breathing.

In pranayama, we learn to delay the action of the diaphragm and let the laterally expanding ribs initiate the in breath. The perimeter of the diaphragm is then activated to lengthen down to the feet as the ribs continue to widen. This allows the lungs to expand fully. On the exhalation, the ribs are reluctant to release. The diaphragm, with the help of an activation of the abdominal muscles, begins to slowly release up into the chest cavity. As the diaphragm rises up, the ribs slowly begin to release in and down around the diaphragm. Find a comfortable position, lying or sitting, and explore your own breathing process. Stay soft in the eyes, ears and throat. Let the spinal muscles completely relax.

Notes for teachers.

Why do you want to teach? This is a personal question, and usually will not change over time, especially if you are born as a teacher. You can’t help it.

What do you want to teach? Music? Art? Science? Cooking? Yoga? Ah, yoga. What kind of yoga? Lots of brand names and approaches. Which of those is an expression of you, who you are in this moment? If you find yourself teaching for many years, you will find that your sense of what yoga actually is will evolve. Hopefully you discover and develop your own unique approach to teaching. Ultimately, all of us are unique. Cloning does not work in teaching spiritual practice.

How will you go about teaching this? What skills, practices, investigations will you use to help in the awakening of the students who come to you? How will you integrate yoga philosophy, yoga science, meditation to the teaching? What poses will you emphasize? These answers will be constantly changing, if you yourself are practicing, inquiring, exploring the world.

We must also study the effects of the postures. Where are the weak links in the body that might be compromised? How can you adjust or support the students to experience a healthy action? In which ways may the students misunderstand your instructions? Words are very limited in describing postural actions.